DELL RAPIDS, S.D. – Sara Holmberg’s job as a counselor at Dell Rapids Middle School has never been more challenging.

As fallout from the pandemic creates what the U.S. Surgeon General calls a “youth mental health crisis,” school counselors like Holmberg find themselves providing not just academic and vocational guidance, but emotional support to students and families. Forging that many personal connections is difficult, so schools are exploring ways to supplement traditional counseling with professional partnerships to make sure teens get the attention they need.

Holmberg, 38, is one of three counselors in the Dell Rapids School District, which has 985 students. Now in her fourth year at the school, she is the only counselor serving the middle school, with an enrollment of about 300. She knows there is no way she can provide effective one-on-one guidance for every child, especially as more students and families continue to struggle with academic and financial setbacks from COVID-19.

According to the South Dakota Department of Education, nearly 90% of accredited schools in the state held in-person classes during the 2020-21 school year, alleviating some of the loss of structure from when schools went to remote learning for nearly three months starting in March 2020, when coronavirus first hit the state.

And yet, many students continue to suffer emotional problems. Nationally, 37% of high school students reported they experienced poor mental health during the pandemic, according to a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention survey released March 31, while 44%reported they felt sad or hopeless during the past year.

This continues a trend seen before the pandemic, when a CDC data summary from 2009-19 found that more than 1 in 3 high school students said they had experienced such persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness in the past year that they couldn’t participate in their regular activities, a 40% increase from the previous report.

In South Dakota, suicide was the 10th-leading cause of death overall among all state residents in 2020 but was the leading cause of death among ages 10 to 19, according to the Helpline Center, a statewide suicide prevention agency. The crisis is particularly staggering for Native American youth, whose suicide rate is estimated by the South Dakota Department of Health to be 2.5 times higher than the white population, with social isolation during the pandemic increasing the emotional toll.

“The pandemic put mental health more on the radar and accelerated everyone’s concerns,” Holmberg said after meeting with a group of eighth-graders in her office on a recent school day. “Instead of it being part of background conversation, it brought those concerns to the forefront and became in many ways our main focus.”

Getting students involved

Leah DeHaan, a junior at Platte-Geddes High School, recalled her reaction when the school started a student-led “Hope Squad” to tackle suicide prevention and encourage communication about topics such as depression, anxiety, bullying and abuse.

“I was skeptical,” said DeHaan. “As a teen who has suffered from mental health issues myself, I was concerned that it was just shifting responsibility off the adults and onto the students, like they were using students as makeshift therapists.”

She had a conversation with Platte-Geddes school counselor Sadie Hanson, who assuaged DeHaan’s concerns and told her that the fact that she voiced them made her a perfect candidate to serve on the Hope Squad, which now has 15 members spanning grades 7-12.

The national program was created by former Utah high school principal Greg Hudnall, who said he reached a breaking point in 1997 after getting a phone call that one of his students had killed himself in a public park – one in a string of tragedies in the school district.

“That’s when I told myself, ‘I’m done. I can’t take any more of this,’” Hudnall told People Magazine in 2019. “I vowed that I would do everything I could to prevent it from ever happening again.”

Hope Squad programs operate in 35 U.S. states and Canada, with Platte-Geddes and Flandreau building teams in South Dakota. Students are asked to name three peers they would turn to if they were struggling emotionally. Those lists help educators choose team members, who are trained on how to recognize signs of suicide contemplation and depression.

“Studies show that teens who (die by suicide) typically tell a friend that they’re planning to do it, but that peer doesn’t always go to an adult or find a resource to help,” said Platte-Geddes superintendent Joel Bailey, adding that the phenomenon can be more pronounced in smaller communities.

Regardless of population, though, state data point to the need for new strategies. South Dakota’s 2019 Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System revealed that 23% of high school students said they considered suicide, while 12% said they attempted suicide.

DeHaan, who plans to major in history in college and possibly work as a museum archivist, said she struggled with depression and anxiety in middle school and the beginning of high school. Her breakthrough came when talking candidly to Hanson, the school counselor, about what she was going through.

“Slowly we broke it down, and it became easier to discuss,” DeHaan said, “Now you see more kids around here willing to talk about their own struggles, the medications they need to take, and how they plan to move forward.”

Seeking a team effort

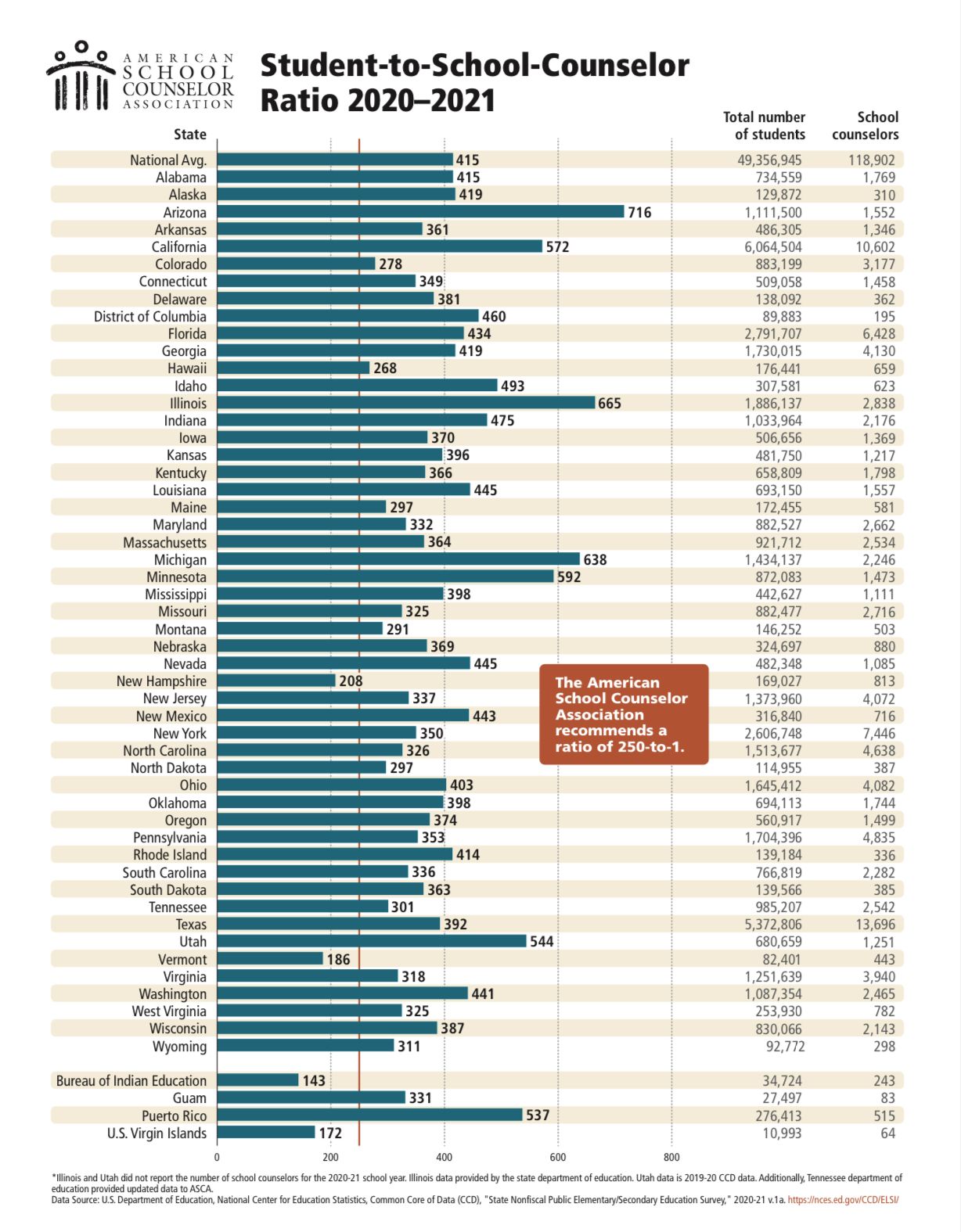

At last count, there were just under 25,000 students in the Sioux Falls School District and 66 school counselors, which equates to a ratio of 364 students to every counselor. That’s right on the state average for South Dakota and on par with ratios in neighboring states Iowa (370:1), Nebraska (369:1) and North Dakota (297:1). The American School Counselor Association recommends a lower ratio of 250:1.

“Building the new high school (Sioux Falls Jefferson) helped with the ratios, but we could always use more support,” said Travis Sieber, who heads the counseling department at Washington High, which has six counselors for 1,870 students.

“Sometimes the mental health related duties become so top heavy that there aren’t enough hours in the day to address other aspects of the job, like academic support and post-high school planning.”

Sieber, in his 14th year at Washington, saw slippage in student performance following the spring of 2020, when classes went online. That loss of structure and in-person interaction fostered bad habits that were hard to break, he said, not to mention pandemic-related hardships faced by many families.

“For the first time in any of our generations, adults didn’t have all the answers when it came to safety and housing and a sense that everything would be OK,” said Seiber. “That created a sense of heightened anxiety that was passed down to students.”

This year, Washington’s counseling department set up a weekly programming series called the “Warrior 24,” an effort to address 24 mental health topics over 24 weeks for 24 minutes every Thursday. The group surveyed students to find out their top concerns, which ranged from “burnout or pressure from activities” to “sleep issues and time management” and “stress and anxiety management.”

Help is also available outside the school, with medical providers such as Avera Behavioral Health, Southeastern Behavioral Health and the Lutheran Social Services PATH program partnering with the school district and taking on referrals. The Helpline Center offers a Text4Hope program that provides crisis texting support for all high school students in the state.

For most students, though, it helps to have a guiding hand and familiar face in the school hallways to enhance the educational experience. Sioux Falls used federal Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER) funds to add seven more school counselors for 2021-22, encouraging them to actively engage with students rather than waiting to be consulted.

“It’s important to get counselors into the classrooms not only for academic support, but social/emotional support and the college/career aspect,” said Patti Lake-Torbert, coordinator of counseling services for the state’s largest school district. “That is where the hope comes from because we all need to know what our ‘why’ is, such as ‘Why am I in school?’ We want to make sure students know that we believe in them and their ability to make decisions about what they want their future to look like, and we’re here to help.”

Putting families in focus

In Dell Rapids, Sara Holmberg and her fellow counselors know that encouraging mental health conversations when appropriate is a team effort that stretches into households, where real solutions await.

“Even if I could meet with every kid, I don’t know their family dynamics,” Holmberg said. “Everything might be fine one day and there could be a family crisis soon after.”

Dell Rapids superintendent Summer Schultz started looking for ways to expand the school district’s outreach after seeing mental health concerns bubble to the surface during the height of the pandemic.

“The wheels had been turning for a while,” said Schultz, president-elect of the South Dakota School Superintendents Association. “We had all been searching for mental health support and exploring ways to fund it. But it’s heightened when families are dealing with repercussions of COVID-19 – losing family members, losing income or jobs, kids at home, rising inflation. These issues are not diminishing as things begin to become more normal. And when one person is suffering, the whole family suffers.”

In partnership with the Utah-based Cook Center for Human Connection, Dell Rapids offers “virtual mental health nights” with online support for families from trained professionals. That program will be expanded using ESSER funds to provide a family coaching component, where parents have 24/7 access to consultants who can help with everything from behavioral issues to making a household schedule.

The school district also is utilizing an animated series called “My Life is Worth Living” created by Terry Thoren, who helped produce the “Rugrats” television show on Nickelodeon in the 1990s. The character-driven YouTube videos focus on topics such bullying, suicidal ideation, sexual orientation and abuse.

“The series does a really good job of modeling for parents,” said Holmberg. “It gives them the language to talk about these things. Sometimes parents don’t want to push too much, so this serves as an icebreaker.”

She recommended the video series to a student who was struggling with anxiety and depression. “After watching it, they had the language to talk to me about it,” she said. “They said, ‘I feel anxious and can’t catch my breath. I don’t see anyone else struggling with this.’”

Holmberg responded by saying that in the video, there were trusted people to speak with – and encouraged the student to consider peers or adults to share experiences with. “It helped them not be so tunnel-visioned on their own crisis,” she said. “It opened up a lot of possibilities.”

The hope among educators is that those possibilities will increase as new strategies and awareness emerge, protecting and inspiring students at a time when they need it most.

“One thing that the pandemic and other social events have done is bring mental health to the forefront,” said Seiber. “The stigma is slowly going away as young people are more willing to ask for help. I think we’re headed in the right direction.”

How to get mental health help and watch video series

Resources to get help for yourself or someone else who may be considering suicide:

The Helpline Center: Callers across the state can obtain county-specific resource information and be connected to a suicide hotline.

- Call: 211 or 1-800-273-8255

- Text: Text your zip code to 898211

- Front Porch Coalition: 605-348-6692

National Suicide Prevention Lifeline/Indian Health Service hotline: 800-273-8255 (TALK)

Crisis Text Line: Text CONNECT to 741741

Animated Series: mylifeisworthliving.org