PHILIP, S.D. – In the next six months, two cities will arise on the South Dakota prairie with populations larger than most of the existing towns west of the Missouri River. Two similar cities will be built in 2020.

The temporary towns will exist for up to two years, include several dozen buildings and each be inhabited by up to 1,400 workers, mostly well-paid in their 20s, 30s and 40s.

The residents will work long hours, six days a week, and then have Sundays free to hang out, do laundry and likely stream into nearby towns such as Buffalo, Opal, Philip and Colome, communities with populations ranging from almost zero to around 900 residents.

The workforce camps, also known as “man camps,” will house, feed and care for thousands of men and women who will arrive in South Dakota in 2019 as part of the massive effort to build the Keystone XL Pipeline through nine West River counties.

For some who now live and work along the pipeline route, the workforce camps are the most concerning – and also the most curious – element of the construction project that will bury a 36-inch oil pipeline along a roughly 250-mile stretch of western and central South Dakota.

The workforce camps, the influx of people and the potential for costly or violent protests over the controversial pipeline are hot topics of conversation along the route.

Depending on who you talk to, construction of the pipeline through South Dakota will go one of two very different ways.

Some believe the construction work and arrival of thousands of highly paid employees will bring a burst of prosperity to sparsely populated rural areas that had no other realistic hope for such a sudden, significant economic windfall.

Yet others worry the project will cause traffic risks and crime, alter the peaceful pace of small-town South Dakota life, or attract protests that could get violent and cost millions to manage.

Plans for the project that will start next spring are moving quickly as builder and owner TransCanada Corp. rushes to start construction of the $8 billion pipeline next summer. Trucks hauling gravel to beef up country roads are already commonplace and some land is being cleared on the pipeline path.

As the project comes into focus, many of the people along the route are considering how to prepare as they either hope for the best or anticipate the worst.

Worry permeates pipeline process

Right now, the land across Highway 73 from where 68-year-old Maralynn Burns lives in Haakon County is a barren stretch of rolling South Dakota prairie.

By June, that pastureland will be transformed into a bustling city of up to 1,400 people who will live, travel daily to and from nearby work sites and recreate nearby.

Like many residents of areas where the Keystone XL will be built in South Dakota, Burns has more questions than answers about what life will be like during construction. Yet, she is certain that the comfort of her daily routine will be lost.

“The man camp is what makes me nervous,” Burns said recently from behind the counter of Petersen’s Variety store in Philip where she sometimes works. “I’ve never locked my door or taken my keys out of my automobile. I guess I’m going to have to find my house keys now.”

Burns calls the construction of the pipeline and its potential impacts on Haakon County “the best kept secret in Philip,” and “a pretty big deal.” She wonders if more local police will be needed, if traffic will stall at shift changes or what may come when more than 1,000 people take up residence in an area known for cattle sales, quiet living and frequent conversations among locals who almost all know one another.

“Change is hard for us old ones,” she said. “We’re still here because we like our small town and the life here.”

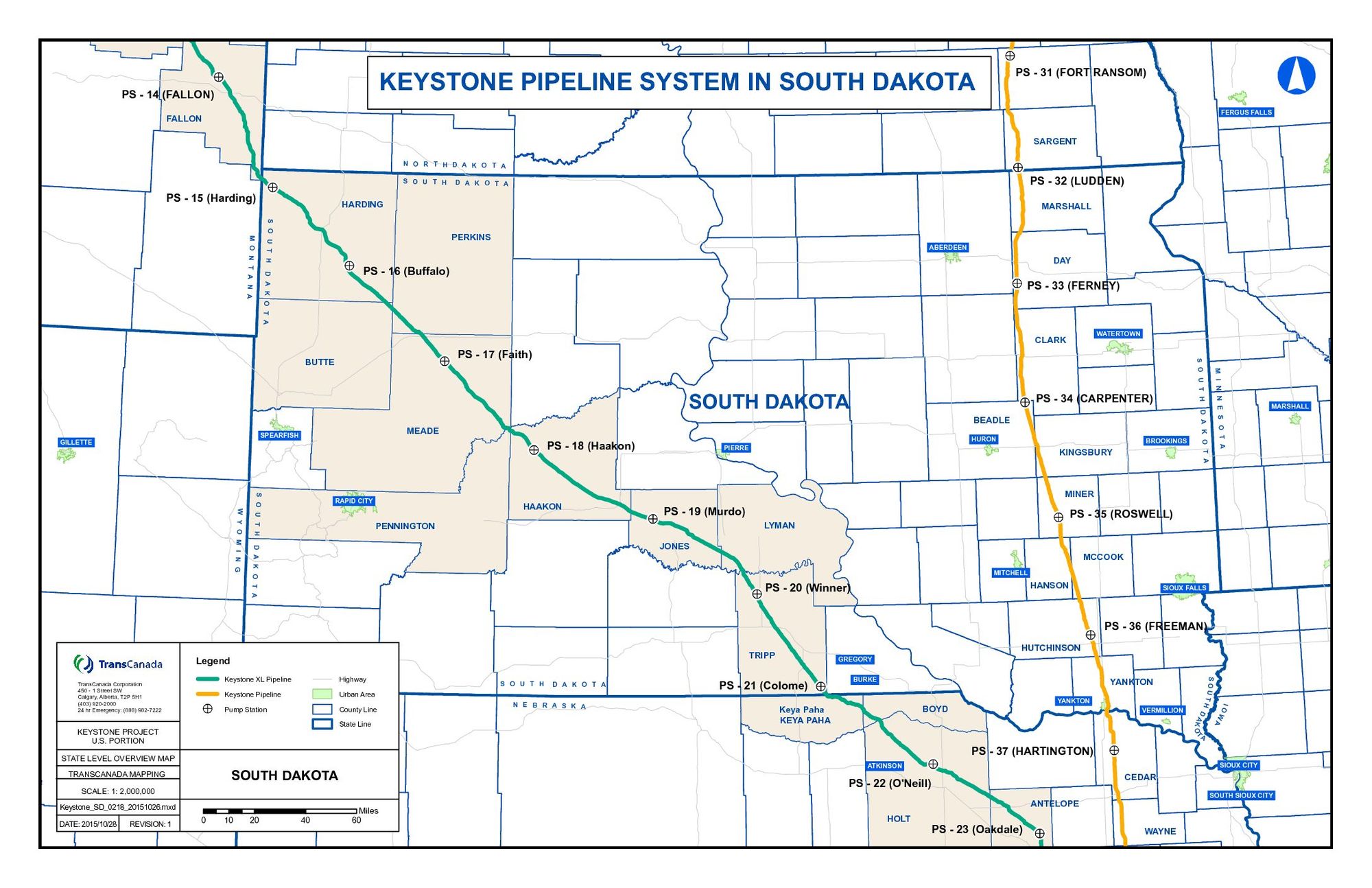

The pipeline route through South Dakota will run northwest to southeast from Harding County through Butte, Perkins, Meade, Pennington, Haakon, Jones, Lyman and Tripp counties before moving into Nebraska.

The pipeline is being built by TransCanada to move crude oil from Alberta, Canada, through Montana and South Dakota, to Steele City, Neb. where it will merge with existing pipelines headed to refineries in Texas. Backers of the pipeline say it is the safest, most economical way to move oil and will help reduce American reliance on oil from less-stable Middle Eastern nations.

Opponents argue that the pipeline will be prone to leaking, is being built through sensitive Native American historical sites and natural landscapes that should be protected, and amounts to subsidization of a foreign country’s quest for money. The pipeline was first proposed nearly a decade ago, then was blocked by former President Barack Obama and finally reinstated by President Donald Trump shortly after he was inaugurated. Construction in South Dakota will start in summer 2019 and run about two years; work will be halted during winter months.

The chance that major protests could arise is causing the most concern for government and law enforcement officials, especially in places like Harding and Haakon counties which each has only a sheriff and one deputy. Those and other rural counties have few government resources. Some rural counties have no jails to house arrestees. Protests over the Dakota Access Pipeline in North Dakota in 2016-17 cost local and state governments more than $38 million to manage, and in South Dakota local counties would be expected to pay significant costs before state disaster aid would flow in.

“We’re worried about the protesters and those sorts of things we may have to spend money on — the court system and holding them and all that good stuff,” said Barb DeSersa, auditor for Tripp County, which will be home to a workforce camp and about 55 miles of the pipeline. “People are just kind of nervous as to what’s going to happen.”

The pipeline is being built mainly on private land in South Dakota and most property owners have already signed easements for construction. The South Dakota section will not cross through any American Indian reservations.

Many local officials are also worried about safety on two-lane rural roads that soon will carry thousands of loaded semi-trucks and passenger vehicles. The camp will be located less than a mile north of Philip on state Highway 73, one of the two main roads through the town.

“In the morning all those people will leave there, and some may ride a bus but people will be driving their own outfits and there will be a truck yard there,” said Haakon County Commission Chairman Stephen Clements. “So, you could have 300 to 500 vehicles come rolling out in the morning.”

Concerns have also arisen over the impact an influx of workers will have on small-town schools, hospitals, and other service providers and agencies that are not prepared to handle hundreds of people arriving almost all at once.

“When they say 1,400 workers will come in here, it kind of puts the fear of God in you because we don’t have the facilities to handle that number of people,” said Clements, who is mostly optimistic about outcomes of the construction process.

Outside of any significant protests, the largest impact on local residents – both positive and negative — will likely come from the four workforce camps that will be built and operated by a Texas firm called Target Lodging.

Target Lodging has furnished housing for dozens of prior projects ranging from major concert events to temporary disaster housing to workforce camps in the North Dakota oil fields and at the Olympic games in Salt Lake City, Vancouver, Canada and Athens, Greece. A spokesman for the company declined an interview request by South Dakota News Watch, but according to the firm’s website, all functions are geared to keeping residents comfortable and ready to work. Housing units often resemble modular homes with private rooms and beds. Food options include prime rib steaks, hand-cut French fries, handmade pizzas and the option for healthier foods. Common areas provide space for workout equipment, games like foosball and outdoor sporting activities.

TransCanada offers assurances

TransCanada representatives have assured South Dakota officials along the route that the workforce camps – which will house from 600 to 1,400 people each – will have minimal impact on their communities. The sites are monitored by a private security team, are surrounded by fences and gates, and entry is allowed only to badge-carrying employees or approved guests through a guarded entrance.

Buses will transport many workers to and from job sites. Alcohol is allowed in the camps but is not sold on site, TransCanada spokeswoman Robynn Tysver said.

“These people are free to come and go, and we hope they explore their local communities, maybe see a movie or visit South Dakota tourism sites,” she said.

TransCanada representatives have traveled the pipeline path through South Dakota to answer questions and assuage concerns of local officials; company official Robert Latimer is now on a first-name basis with many West River officials.

Company officials say that while traffic and the potential for protests are understandable concerns, the worries over the workforce camps should be minimal.

“People have this idea that it will be a wild city and it’s not going to be like that,” Tysver said of the workforce camps. “Those people are there to work.”

Tysver also stressed that TransCanada employees are subject to pre-employment and random drug tests and a strict code of conduct which if violated can get them kicked out of the camps. Unlike the oil fields of North Dakota, where many firms operate, employees on the pipeline route would have few if any options for employment if they lost their job with TransCanada.

According to the roughly 300 pages of planning documents filed in Meade County for the camp near Opal, the site will feature about 20 buildings including 16 dorms, a commissary, a medical clinic, barbershop and recreational hall. The camp near Philip will include 1,100 beds and 300 sites for recreational vehicles.

Despite assurances from TransCanada, not everyone is convinced that no trouble will arise from the camps.

“These hard-working men always find a way to get entertainment, either on camp or in the vicinity,” said Marvin Kammerer, a longtime resident of Meade County. “That means more crime, more women coming in.”

The pipeline path will also be home to several permanent oil pumping stations and temporary equipment staging areas that will bustle with activity during construction.

TransCanada is now improving roads to handle more truck traffic and, under agreements with the counties, is responsible to return local roads to their pre-construction condition after work ends.

Businesses expect a boost

When an unexpected happenstance dramatically boosts the bottom line of a business, it’s not easily forgotten.

Philip restaurant and bar owner Don Carley said his father, a retired restaurateur, still sometimes brings up how much his business boomed in the 1960s when Interstate 90 was detoured through Philip at the same time the military was building missile sites in western South Dakota.

While Carley isn’t sure what to expect from the pipeline construction, he has his sights set on making some extra money at The Steakhouse, a sit-down restaurant and full bar he runs in downtown Philip.

Carley doesn’t open the restaurant on Sundays, but he may reconsider that approach once the pipeline crews move in. “You’ll always have people who want to go have some drinks and a good meal,” he said. “Or if they want to watch a football game or baseball game, where else are they going to do that?”

Like others, Carley doesn’t relish the thought that protests could follow the construction into Philip. He said he will also be vigilant about preventing any fighting that might occur if people get out of hand in his bar.

With a successful business already going strong, Carley said he will take the entire situation in stride. “I’ve never had anything bother me, so I don’t mind this deal at all,” he said.

Others in Philip are expecting a revenue windfall from the pipeline construction. Jason Petersen, owner of Rock N Roll Lanes on U.S. 14, plans to plunk down $200 for a permit that will extend his liquor sales permit to include Sundays, when pipeline employees will be off work.

“It’s basically going to triple the size of Philip over a period of 18 months, and all the local businesses are talking about it,” said Petersen, whose bowling center has eight lanes, a diner and attached bar area. “If it could boost thousands of dollars in income in a month’s time, that would be amazing for our economy and for me.”

Governments should also see a benefit from user fees, permits and tax collections.

In an email to News Watch, Tysver said the economic benefits of the pipeline to South Dakota and the entire United States will be significant.

She quoted a U.S. Department of State report that estimated in 2014 that pipeline construction will create 3,000 to 4,000 new direct and spinoff jobs in South Dakota, including welders, pipefitters and laborers as well as at local establishments that will serve the workforce. An estimated $100 million in wages could be created, the report said.

Furthermore, Tysver wrote, South Dakota counties will see about $20 million in new annual property tax revenues.

Meade County commissioners recently learned that permit fees paid by TransCanada had already topped $215,000. Clements, the Haakon County commissioner, said his county expects to receive about $350,000 in new annual taxes from the pipeline and its construction.

Matt Reedy, vice president of First National Bank in Philip who serves as treasurer of the local chamber of commerce, said local businesses may see a bump but he doesn’t expect the pipeline project to create a sea change in the local economy.

“As far as economically for the town, I don’t know that it will mean much. We’re a small town and the doors shut on everything after about 6 or 7 at night except the bars and the movie theater and the bowling alley,” Reedy said.

Yet six months before any major work begins, Reedy said he’s seen some spin-off benefit for local industry as TransCanada has hired local crews to dump and grade gravel on rural roads in the area.

“They’ve hired every local guy that can drive a semi and haul a gravel trailer, and they’re all filling up at the local stations,” Reedy said.

Even if the workforce camp provides most basic needs for employees, Reedy said workers will still need to get away. “It has to have a good effect,” he said. “Even if you’re staying at a self-contained area, you’re still going to go to a convenience store and get something different now and then.”

Some entrepreneurs began gearing up years in advance to accommodate the pipeline workers. DeSersa, the auditor in Tripp County, said she knows of people who bought rental property long ago in hopes that pipeline workers may move in temporarily or even permanently once construction begins.

The mood is much the same in Buffalo, home to about three eateries and watering holes and several other businesses that may see new revenue from pipeline workers. Locals could also land jobs working for TransCanada during construction.

“I think there’s a lot of mortgages that will be paid off,” said Kathy Glines, auditor and emergency manager for Harding County. “I’m telling the businesses, this is two years of Christmas and you don’t have to compete with Amazon or with Walmart — and it’s a captive audience.”